by

Robert Cauneau

2 December 2024

Introduction

In economic debates, one assertion constantly recurs: the public deficit is financed by private savings. This idea, while intuitive, is based on a profound misunderstanding of modern economic mechanisms. Equating the state with a household or a business, forced to « find funds » to spend, distorts the perception of accounting and macroeconomic reality. The public deficit is not a financing need, but an essential lever that injects financial resources into the economy.

Using accounting frameworks and basing itself on sectoral financial balances, this article aims to show that the public deficit fuels the private sector’s net financial savings, and that the reverse cannot be true.

This article focuses on the accounting relationship between the public deficit and private net savings, the latter without distinguishing between the domestic and foreign portions. It therefore does not address the impact of the public deficit on the trade balance. This aspect will be addressed in another article.

Money is Accounting

Accounting plays a fundamental role in understanding money and its dynamics. This is because one agent’s expenditure is necessarily another agent’s income. Double-entry bookkeeping is therefore an essential tool for understanding and analyzing flows. Yet, surprisingly, it is underutilized in economics, considered a minor art, particularly because it reveals nothing about the behavior of agents. Mainstream economic analysis favors mathematical models, which often neglect these accounting foundations. This choice marginalizes an approach that is nevertheless essential for grasping the reality of financial flows and sectoral balances.

Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) emerged largely through a description of monetary transactions as accounting transactions involving the government, banks, businesses, and individuals. However, MMT economists are well aware that an accurate understanding of accounting is not, in itself, a theory. Thus, Scott Fullwiler, one of them, states1 that:

« Any relevant theory simply has to conform to real-world accounting as a basic criterion, and, moreover, it is precisely this sort of basic understanding of accounting that is quite often absent from economic theories and from the way the public and policymakers discuss and understand economics. […] It is therefore not surprising that the economics profession as a whole continues to step on each other’s toes when it comes to understanding the monetary system. »

The same is true for L. Randall Wray, who recalls the insistence his teacher Hyman Minsky2 placed on the need to understand the movement of balance sheets, in order to master the functioning of the monetary system, telling these students: « Go home and do the balance sheets, because what you’re saying is nonsense. » » He also recounts how Warren Mosler, the father of MMT, managed to convince him of the relevance of MMT by using accounting schemes, in particular the fact that any public expenditure systematically generates an increase in bank reserves3, which encouraged him to deepen his own knowledge of the movement of balance sheets, and led him to conclude that Mosler was right.

Reasoning in Net, Not Gross

It is first necessary to explain why, in this demonstration, it is necessary to use net financial savings and not gross financial savings.4 This explanation lies in the fact that, while gross savings certainly include all financial assets held, they ignore the corresponding liabilities, providing an incomplete and therefore misleading view. Indeed, net savings, which subtract liabilities from assets, reflect effective financial capacity. For example, a bank deposit (gross asset) often corresponds to a loan (liability), canceling out any net wealth creation. It follows that net savings are decisive for the economic decisions of private sector agents because, unlike gross savings, it influences their ability and willingness to consume or invest. Only the public deficit can contribute to the net financial savings of the private sector.

The following discussion aims to demonstrate, using accounting diagrams, that only the public deficit can contribute to the net financial savings of private sector agents, and that the converse cannot be true.

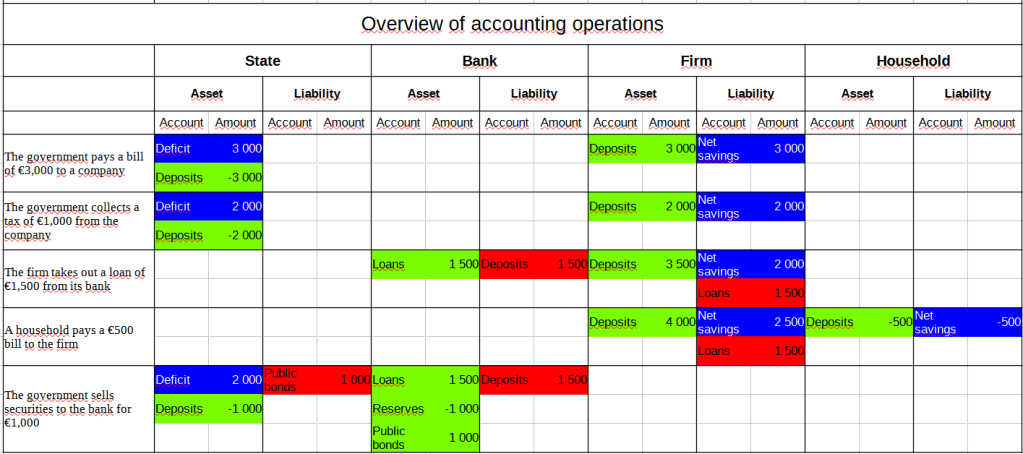

A few preliminary clarifications are necessary:

- By construction, due to the double-entry accounting principle, the debit of one account generates the credit of another. Thus, the assets and liabilities of the balance sheets always balance.

- The examples are intentionally simplified. In particular, they do not take into account any initial situation, which can generate abnormally negative balances, but this in no way detracts from the underlying logic, and therefore from the demonstration.

- From the second transaction onward, each transaction is accumulated with the amount appearing in the previous transaction. Each transaction therefore represents a stock, not a flow.

- The use of colors (blue for the government deficit and net savings of private sector agents, green for asset transactions, red for liability transactions) is intended to facilitate understanding of the processes.

The accounting transactions to be studied are as follows:

- The government pays a bill of €3,000 to a company: This transaction shows that when the government spends, its deficit and the net savings of the beneficiary company increase, in this case by €3,000.

- The government collects a tax of €1,000 from the company: The financial movements are the opposite of those in the previous transaction. The government deficit and the firm’s net savings decrease by €1,000.

- The firm takes out a loan of €1,500 from its bank: The firm’s deposits and loans increase by €1,500. But, since the loan must be repaid, the transaction affects both the firm’s assets (deposits) and liabilities (loans). Therefore, its net savings remain unchanged.

- A household pays a €500 bill to the firm: The household’s net savings decrease, and the firm’s net savings increase by the same amount of €500. The total net savings of the private sector (firm and household) therefore remains unchanged.

- The government sells securities to the bank for €1,000: The government’s deposits increase, but only the form of the money changes, moving from « reserves » to « securities » at the bank. The quantity of money does not change. The government deficit and private sector net savings remain unchanged.

In summary, only operations 1 (public spending) and 2 (tax collection) affect the level of net financial savings in the private sector. Operation 4 (payment by a household to a business) generates a transfer of net savings between private agents, but the sector’s net savings remain unchanged. Operations 3 (bank loan) and 5 (sale of government securities) have no impact on net savings.

Therefore, from an accounting perspective, the public deficit has a direct impact on the level of net savings of private sector agents. Conversely, the private sector, which lacks the ability to change the total amount of net savings in the economy, cannot finance the public deficit in any way. This asymmetric relationship reflects the government’s unique position as the monopoly issuer of its currency.

The table below provides an overview of these five operations.

Sectoral Financial Balances: A Graphic Illustration

The sectoral financial balances approach,5 put forward by MMT economists,6 clearly illustrates the structural relationship between public budget deficits and private sector net financial savings. This approach is based on an essential accounting identity, which holds true in all countries: the sum of the public and private sector balances is necessarily equal to zero. In other words, if the private sector wishes to generate net savings, then the public sector must record a deficit of the same amount.

This accounting identity, although seemingly simple, perfectly illustrates the logic outlined above: only the public deficit has the capacity to generate net savings for the private sector, because the latter, as a user of money and not as a creator, cannot, on its own, increase its net savings.

This analysis removes any ambiguity regarding the direction of the causal link between public deficit and private savings: it is the former that feeds the latter, and not the other way around. Any contrary interpretation, which would assume that private savings finance the public deficit, is based on a lack of understanding of the accounting foundations of the system.

Conclusion

An accounting analysis of the monetary system unambiguously demonstrates that the idea that private savings finance the public deficit is based on a misconception. This widespread confusion fuels political and economic discourse favoring austerity policies, to the detriment of collective well-being.

Far from being an aberration or a threat, the public deficit constitutes a necessary condition for macroeconomic stability. By allowing the private sector to build its net financial savings, it plays a key role in supporting the economy and responding to economic fluctuations.

Faced with social, economic, and ecological challenges that require massive investment, it is imperative to rethink our understanding of the role of the public deficit. By drawing on accounting realities, public decision-makers could design less constrained public policies and therefore more focused on the real needs of citizens.

Notes

1. Scott Fullwiler’s article can be accessed here : https://mmt-france.org/2019/06/01/la-mmt-une-introduction-aux-realites-operationnelles-du-systeme-monetaire/

2. See this article : https://multiplier-effect.org/modern-money-theory-how-i-came-to-mmt-and-what-i-include-in-mmt/

3. See this article : https://www.levyinstitute.org/pubs/wp_961.pdf

4. Considered in the context of the state’s monopoly on its currency, the concept of « Net Financial Assets » (NFA), which overlaps with that of net financial savings, is at the heart of MMT. It distinguishes MMT from all other monetary approaches, both orthodox and heterodox, which reason in gross terms, not in net terms. In the logic of MMT, NFAs are the financial basis on which the economy rests; it is the financial wealth that remains with the economic agent once all his debts have been settled. They constitute the part of financial wealth that does not come from debt (bank credit), but from final payments (in relation to the state through public spending).

5. The article can be read here : https://blogs.mediapart.fr/robert-cauneau/blog/181024/les-soldes-financiers-sectoriels

6. It should be noted, however, that this formalism is not specific to MMT. It is also used by post-Keynesian economists.