By

Robert Cauneau

17 December 2025

Introduction – Understanding a Trajectory Rather Than Pointing the Finger

Since the mid-1970s, French public debt has been on an almost continuous rise. This regularity has instilled a Pavlovian reflex in the public debate: if the debt is increasing, it means the state is either wasteful or poorly managed. The deficit has thus become the expression of a moral failing from which we must free ourselves through sheer willpower.

However, this narrative does not stand up to scrutiny. If the deficit were a freely controlled variable, we would observe proactive budgetary trajectories, independent of crises. But history shows the opposite. The aim of this article is to move beyond the moral perspective to understand the actual mechanics: is the deficit truly “chosen,” or is it essentially “imposed”?

To answer this, we rely exclusively on observable metrics (growth, unemployment, private savings), far removed from opaque theoretical models. An examination of this data reveals a very different reality: the public deficit is not a discretionary lever, but an adjustment variable, closely dictated by the economic cycle and the private sector’s savings behavior.

Public debt, the accumulation of past public deficits, far from being an uncontrolled spiral, thus appears as the accounting record of profound macroeconomic imbalances. This is the factual interpretation we propose, because persisting in treating deficits as mere management choices prevents us from understanding their nature, and therefore from responding to them intelligently.

I – The public deficit : a variable that is imposed, not controlled

This section addresses a crucial question: is the deficit managed by the state or is it a mechanical reflection of economic conditions?

If the deficit were a political choice, it should be proactive and precede crises. However, data analysis shows the opposite. There is a robust and systematic correlation: the deficit increases automatically as soon as growth slows (oil shocks, 2008, 2020) and only decreases when economic activity picks up again.

This observation confirms that the deficit is an endogenous variable. It is not a deliberate choice; it results from automatic stabilizers: when economic activity declines, tax revenues (VAT, corporate income tax, social security contributions) fall, while social spending increases. With no change in policy, the balance therefore deteriorates « on its own » to cushion the economic shock.

Chart 1 – Automatic Stabilizers

It is crucial not to reverse causality. The correlation between deficits and weak growth does not mean that the former causes the latter, but rather that it is a reaction to it. Blaming the deficit for escalating into a crisis is like blaming the thermometer for indicating a fever. The data is clear: economic downturns always precede the deterioration of public finances.

Thus, the increase in debt since 1975 does not signal persistent laxity, but rather an environment where growth is structurally insufficient to absorb these stabilization deficits. The deficit is something that is endured, not sought after.

II – Social Spending: Between Crisis Cushion and Societal Choice

The analysis of the structure of public spending reveals a major fact: as shown in Figure 1, over the period from 1980 to 2024, only the social benefits component has seen sustained growth. The other items (wages, intermediate consumption, investment, etc.) remain broadly stable relative to GDP. Equating this increase with « laxity » is an analytical error.

Chart 2 – Structure of Public Spending as a Percentage of GDP

This increase can be explained by the convergence of three factors:

- The mechanical effect of crises: Automatic stabilizers are fully operational. During periods of economic slowdown, unemployment rises, inflating compensation expenditures without requiring any new budgetary decisions. The Direction de la Recherche, des Études, de l’Évaluation et des Statistiques (DREES) itself acknowledges that « crises are the main causes of the deficits in social protection accounts over the last few decades ».1

- Demographics: The aging population and the retirement of baby boomers increase healthcare and pension needs. These are predictable structural changes, not management failures.

- Policy choices: Even decisions regarding expansion (retirement age, health coverage) often respond to compelling macroeconomic pressure: the need to support household demand or regulate the labor market when the private sector is no longer sufficient. These expenditures are not « gifts, » but essential pillars of social and economic stability.

Recognizing that social spending is structurally higher does not contradict the endogenous nature of the deficit. On the contrary, it confirms it: social protection acts as the ultimate buffer against the imbalances of modern capitalism. The problem is not spending itself, but the inability of the current macroeconomic framework, and in particular the level of employment, to finance it. It is this central link between unemployment and the deficit that we will now examine.

III – Unemployment, the True Driver of the Deficit

While the deficit follows the economic cycle, unemployment is its primary driver. The temporal analysis is clear: since 1985, the rise in unemployment has almost systematically preceded the deterioration of the public balance.

This precedence reverses the usual causality. It is not the deficit that disrupts the economy, but rather the deterioration of employment that deepens the deficit. The mechanism is purely accounting-based: more unemployed people mean fewer contributions (revenue) and more benefits (expenditure). The deficit forms « on its own, » without any active political decision.

The turning point in the mid-1980s is crucial here. At that time, the link between unemployment and the deficit became more rigid. This corresponds to abandoning the goal of full employment in favor of fighting inflation and de-indexing wages. Unemployment becomes a structural adjustment variable, used to moderate wages and curb inflation.

Chart 3 – Public deficit vs. unemployment rate

From then on, the role of the deficit changes: it no longer serves to eliminate unemployment, but to mitigate its social cost. The « take-off » of the debt is therefore not proof of fiscal laxity, but the accounting residue of a system that accepts persistent underemployment.

This is where the analysis converges with Modern Monetary Theory (MMT): persistent unemployment is the symptom of a public deficit insufficient to absorb private sector savings. Paradoxically, we have recurring deficits precisely because they are not calibrated to achieve full employment. The deficit is not « excessive spending, » but the accounting price of our abandonment of full employment.

IV – A Regime Change, Not Laxity

While the previous section demonstrated the mechanical link between unemployment and deficits, it remains to be understood why unemployment has become so persistently entrenched at such high levels. This is not an accident, but the result of a historical regime change.

The explosion of debt is often attributed to a « breakdown » in fiscal discipline in the early 1980s. This laxity thesis is appealing, but false. The data shows that it was not a change in budgetary behavior, but a profound shift in the macroeconomic system.

The Shift of the 1980s: From Prices to Employment

Before 1980, economic shocks were absorbed by inflation (price adjustment) to preserve employment. From the late 1970s onward, the absolute priority given to fighting inflation reversed this logic. Adjustment was no longer achieved through prices, but through quantities, that is, through unemployment, which became a structural variable used to moderate wages and curb inflation (see Figure 3).

The Deficit as a Residual of Underemployment

In this new context, the status of the deficit changed radically. It is no longer a management tool, but the accounting residue of a system that accepts persistent underemployment. A depressed wage bill and weak growth erode revenues, while social spending increases automatically. The deficit becomes structural not because the state « spends recklessly, » but because the economy no longer spontaneously generates full employment.

This explains the failure of austerity policies over the last thirty years: they address the symptom (the deficit) without challenging the system that produces it (underemployment). As long as unemployment serves as an adjustment variable, the public deficit will mechanically play its role as a default buffer.

This observation leads us to the ultimate constraint of this dynamic: the savings behavior of the private sector, which we will examine in the following section.

V – Public deficit and private savings : when businesses stop investing

National accounting: the economy is a closed circuit where the sum of all balances is always zero. For one agent to spend less than they earn (save), another must necessarily spend more than they earn (borrow).

The accounting identity is therefore straightforward: the public deficit is not a leakage; it is the exact reflection (down to the cent) of net savings in the private sector and the rest of the world. But to understand the explosion of debt, we must look at who is saving.

Analysis of sectoral balances reveals a major shift in the 1980s.

Before: Businesses were structurally loss-making (they borrowed to invest), offsetting household savings.

After: Businesses became agents with financing capacity. In a context of sluggish growth and financialization, they now prioritize margins and dividends at the expense of productive investment.

Chart No. 4 – Sectoral balances

An Inevitable Arithmetic Consequence

This reversal creates a mechanical constraint. When households and businesses simultaneously seek to save, another actor must necessarily run a deficit for the system to hold together. In national currency, and given the trade deficit which also drains capital, this role of absorber falls, by accounting convention, to the State.

The structural public deficit is therefore not a management failing, but a reflection of a capitalism where the private sector no longer invests enough. The State does not increase its deficit by choice, but out of necessity, to compensate for the excess savings of a productive sector that lacks markets and prefers financial accumulation to real investment.

VI – The Trap of Weak Nominal Growth

This shift of the private sector towards saving, described in the previous section, has a twofold consequence. Not only does it force the State to compensate, for accounting purposes, but by curbing investment and wages, it stifles the dynamics of prices and economic activity. This is where the trap closes on public finances.

Why do deficits persist, even when the economy emerges from recession? The answer lies in a variable too often overlooked: nominal growth (real growth + inflation).

The revenue engine is stalled.

Public finances are not based on an abstract economy, but on concrete monetary flows (wages, VAT, profits). It is nominal growth that fills the state coffers. However, since the 1980s and the shift towards monetary austerity, France has stifled inflation. We have gone from a regime of strong nominal growth (the Trente Glorieuses) to a stagnant one.

Chart #5 – Public Deficit vs. Nominal Growth

The Impasse of Austerity

This lack of nominal dynamism explains an apparent paradox: the coexistence of constant budgetary efforts and persistent deficits. In an environment of low nominal growth, natural revenues are insufficient. Trying to fill the gap solely by cutting spending becomes counterproductive: it weighs on economic activity, weakens employment, and ultimately reduces the tax base.

The persistent deficit is therefore not proof of laxity, but the symptom of an economy lacking nominal fuel.

Trying to steer the economy by targeting a deficit percentage is a fundamental error. The public balance is a result, not a lever. Making it the priority objective in a context of low inflation inevitably leads to ineffective austerity policies.

One last accusation remains to be examined: does this deficit, whether imposed or not, ultimately weigh on economic growth? This is the subject of the following section.

VII – When the Budgetary Rule Turns the Solution into a Problem

A central paradox emerges: while the deficit is an endogenous variable (dependent on growth and employment), public policies persist in treating it as a controllable variable. As economist Andrea Terzi¹ points out, it is not the deficits themselves that pose a problem, but rather the rules that purport to control them.

Naturally Countercyclical, Institutionally Procyclical

In its natural functioning, the deficit acts as a buffer: it widens during a crisis to absorb the shock and shrinks during a recovery. But setting a specific target ex ante (such as 3%) breaks this mechanism. Terzi perfectly summarizes the impasse, considering that the deficit is countercyclical by nature, but becomes procyclical by regulation.

To meet an arbitrary target during a slowdown, the state is forced to cut spending or raise taxes at the worst possible time. Instead of stabilizing the economy, the budgetary rule exacerbates the recession.

The European Policy Error

This bias lies at the heart of the Monetary Union. By establishing the nominal balance as the sole policy objective for countries with different economic cycles, it becomes disconnected from economic reality (unemployment, investment).

Criticizing these rules is not about advocating for an « unlimited » deficit, but for an appropriate deficit. A balance of -4% may be insufficient during periods of massive underemployment, whereas -1% would be excessive during periods of overheating.

Thus, as long as the deficit is treated as a target to be achieved rather than as an indicator of the state of the economy, it will be perceived as a problem. The rise in debt is therefore also the result of an institutional framework that prevents the deficit from playing its natural stabilizing role.

VIII – Does the public deficit hinder growth?

A pervasive argument saturates the public debate: yesterday’s deficits are supposedly the obstacles to tomorrow’s growth. This intuitive idea, however, rests on a major confusion between cyclical correlation and structural causality.

The Trap of Reversed Causality

In the short term, we do indeed observe that the deficit widens when growth slows. But reading this correlation in reverse is a mistake. The deficit is reactive: growth slows first, causing revenues to fall and social spending to rise. Accusing the deficit of causing the slowdown amounts to reversing the chain of causes.

The Test of Facts (1978-2024)

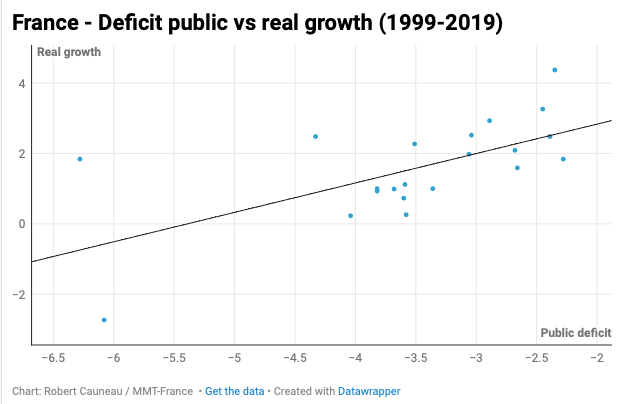

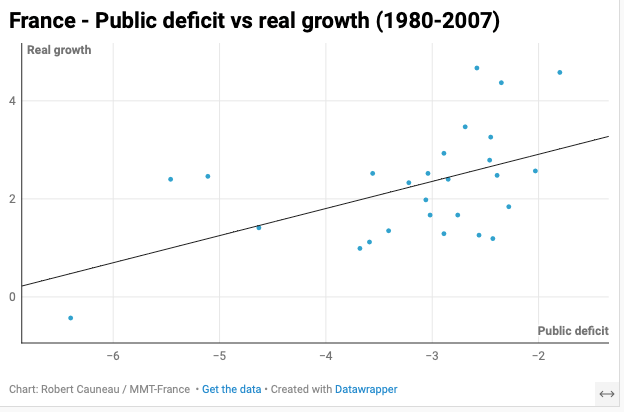

To settle the matter, we must look at the medium to long term. The graphs comparing the deficit and real growth are unequivocal:

Over the entire period 1978-2024, no negative relationship appears. The trend is even slightly positive.

The observation remains the same for each sub-period (1980-2007 and 1999-2019 under the euro). High deficits coexisted with sustained growth, just as austerity often accompanied stagnation.

Chart 6 – Public deficit vs. real growth (1978-2024)

Chart No. 7 – Public deficit and real growth (1999-2019)

Chart No. 8 – Public deficit and real growth (1980-2007)

The Macroeconomic Mechanism

This result is easily explained: the deficit is not a drain of resources, but a net injection of income into the private sector. As long as the economy has untapped capacity (unemployment, underinvestment), this injection supports demand and private savings without crowding out private investment or creating inflation.

The idea that the deficit mechanically hinders activity therefore does not withstand data analysis. The deficit is a response to imbalances, not their cause. Trying to reduce it at all costs is treating the symptom rather than the disease.

IX – A Monetary Perspective: Debt as a Result, Not a Choice

The preceding observations necessitate a break with the usual framework: public debt is not an independent burden, but an accounting entry. As Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) formalizes, the government deficit creates, down to the last euro, the net financial assets of the private sector.

Whether these assets are held as cash (money) or, as current rules require, transformed into government bonds (debt), their accounting nature remains unchanged. What is called « public debt » is therefore, fundamentally, the net financial wealth of the private sector that has not yet been used to pay taxes.

The reversal of causality

Therefore, the deficit is not a discretionary variable that is fixed ex ante. It is the result of private sector behavior. If households and businesses want to save (not spend everything), the government must run a deficit to maintain economic activity.

The deficits that have persisted since 1970 do not reflect « excessive spending, » but rather insufficient net spending to achieve full employment in the face of a strong desire for private savings.

The error of rigid rules

This is why budgetary rules (such as the 3% deficit limit) are counterproductive. They reverse the logic by forcing the real economy to adapt to arbitrary accounting targets, transforming a macroeconomic outcome into a political constraint, at the cost of persistent unemployment.

As for debt interest payments, they constitute income for the private sector. They raise a question of distribution (who receives them?), but are not a macroeconomic drag as long as real resources are available.

Thus, public debt should no longer be seen as an anomaly to be corrected, but as the faithful accounting record of a system characterized by insufficient private demand and a tolerance of underemployment. Trying to reduce the debt without addressing these underlying causes is a dead end.

Conclusion – Rethinking debt to break the deadlock

An examination of the trajectory of public finances since 1975 leads to an undeniable conclusion: the continuous increase in debt is simply the mechanical accumulation of deficits that were not chosen, but rather imposed.

The data proves it: the public deficit does not result from a relaxation of discipline, but rather reacts to shocks, unemployment, and the private sector’s need for savings. Therefore, public debt is not a management failing, but the inevitable accounting entry of a constrained economic framework.

This explains the failure of austerity policies. By targeting the public balance as an isolated choice, they ignore the mechanisms that generate it: weak nominal growth and persistent underemployment. The deficit inevitably reappears because the structural causes remain unchanged.

The fundamental error lies in the confusion between public and private debt. In a modern monetary economy, government debt represents the net financial wealth of the private sector. It is not a burden to be repaid before bankruptcy, but the necessary accounting record of past macroeconomic choices.

Therefore, the question is no longer « how to reduce the debt? » but « what kind of economic system do we want? » A system that tolerates underemployment mechanically produces recurring deficits. Conversely, as Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) suggests, using the deficit to aim for full employment and real stability (rather than arbitrary financial ratios) is the only way to make the trajectory sustainable.

Public deficits and debt are indicators, not a fault. Getting out of the current impasse requires less accounting « rigor » than economic clarity.

Notes

- See this article by DREES : https://drees.solidarites-sante.gouv.fr/sites/default/files/2022-12/CPS2022-Fiche%2003%20-%20La%20protection%20sociale%20depuis%201959.pdf

- See this article by Andrea Terzi : https://mmt-france.org/2022/04/04/relier-les-points-la-dette-lepargne-et-la-necessite-dune-politique-budgetaire-de-croissance/