by

Robert Cauneau – MMT France

Introduction

While France is going through a crucial period of budgetary discussions, the debate is once again focused on the public deficit and debt. In the background, the financial markets appear as essential arbiters, which should be appeased to avoid an increase in interest rates. This vision, which exaggerates the power of the markets over our economy, is largely based on political choices stemming from neoliberal ideology and imposed by the strict rules of the Eurozone, those of the Lisbon Treaty. This self-imposed budgetary straitjacket locks Member States into a financial logic that prevents budgetary management fully oriented towards the well-being of populations.

The billions of euros paid each year in interest only feed privileged investors, and this situation results from political decisions, not from economic necessities. This article aims to deconstruct the myths surrounding public debt and the supposed role of the financial markets by showing that their power is only a well-maintained illusion and that the financial constraints of the Eurozone are primarily political.

Limits to public spending are not financial

It is first useful to recall that, according to the analysis of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), a State that has a monopoly on the creation of its currency, in a floating exchange rate regime, cannot go bankrupt in its own currency, unless it wants to. The limits to its public spending are therefore not financial, but linked to the availability of real resources, whether technological resources, natural resources, or the workforce.

However, the Member States of the Eurozone are a special case, since they operate within a framework containing financial limits, in reality self-imposed, which are the ratios of 3% of GDP for the public deficit and 60% for the public debt. These limits therefore represent constraints on the budgetary policy of the States, preventing them from achieving the deficit necessary to achieve full employment.

Under these conditions, and to the extent that the national treasury account opened at the ECB must have a permanently positive balance, Member States must obtain tax revenues and issue government securities, which, due to the absence of a guarantee by the ECB, makes them dependent on financial markets and exposed to the risk of default. This situation underlines the need for a reassessment of the budgetary rules within the Eurozone, in order to allow these States to have their full economic potential.

Public debt is not a burden, but a wealth

As shown by the accounting identity verifiable in all countries, public debt is equivalent to the national currency created by public spending and not yet used by the private sector to pay taxes. It represents, to the nearest cent, the net financial wealth of private sector agents1. It follows that public debt is not composed of government securities alone. It includes all of the State’s liabilities, namely cash, bank reserves and government securities. It is important to emphasize that issuing government securities does not create new currency, but simply changes the form of the currency from “reserves” to “securities,” just as an amount is transferred from an uninterested current account to an interest-bearing deposit account2.

Public debt (stock) is the sum of annual deficits (flows). Debt and deficit are therefore closely linked, and so when the government seeks to reduce its deficit by increasing taxes or reducing spending, this reduces private sector savings. In other words, when the government withdraws more national currency through taxes than it creates through spending, this causes austerity.

Government securities are not used to finance public spending

Issuing government securities is a practice inherited from the old fixed exchange rate regimes, which is now outdated. These securities are no longer issued to directly finance public spending, but rather to regulate interest rates, a function that has become less necessary since the ECB began remunerating excess reserves. But also, their issuance makes it possible to offer a risk-free financial asset. It is therefore necessary to question the obligation to issue government securities.

However, in the Eurozone, a clarification is necessary: Article 123 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union prohibits the ECB from granting overdrafts to national Treasuries, forcing them to issue securities. However, euros are created by the ECB when Member States spend, which makes the Eurozone the monopolistic creator of money. Requiring a permanent positive balance on the Treasury account with the ECB is therefore based on a fiction, founded on the idea that the State must manage its cash flow like a business. This constraint has no economic basis. It is purely political and is part of the neoliberal ideology, which sees the State as a bad manager and thus wishes to limit its action.

As Warren Mosler, the father of MMT, suggests, it would be entirely possible to stop issuing government securities. And, in any case, if this issuance had to be maintained to offer a risk-free asset, a zero interest rate policy would be an effective solution in order to limit the influence of financial markets3.

The interest rate is set by the central bank

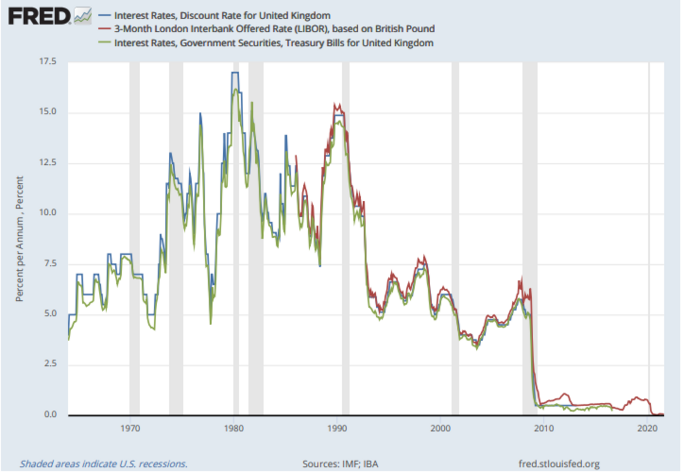

It is essential to understand that movements in interest rates applied to government securities are closely dependent on decisions taken by the ECB. Interest rates are entirely under its control, thus constituting political choices. The observation of interest rate policies in different countries confirms this: the rates applied to government securities follow very closely the central bank’s key rates, as shown in the following two graphs4.

Figure 1 – Interest rates in the United States

Figure 2 – Interest rates in the United Kingdom

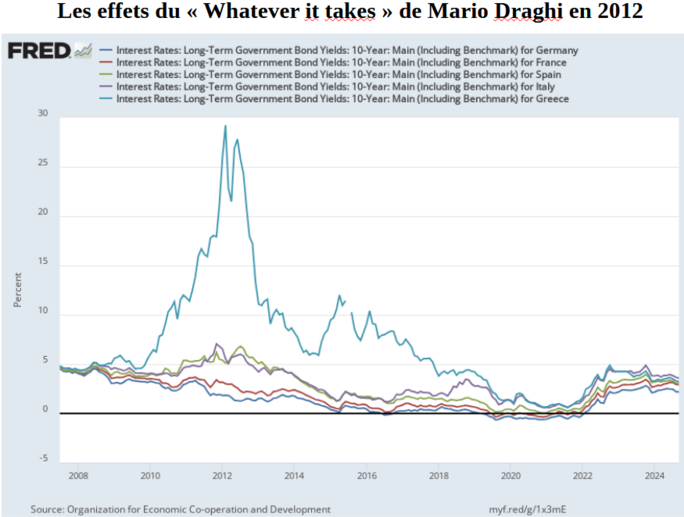

In the Eurozone, Mario Draghi’s “Whatever it takes” in 2012 marked a turning point by bringing interest rates on government bonds back to reasonable levels, particularly for Greece. This event demonstrated in a striking manner that, as long as the ECB guarantees the securities issued by governments, they cannot default.

Figure 3 – Interest rates in the Eurozone

The COVID-19 crisis has also confirmed this power of intervention: the ECB and other central banks have demonstrated that they can counter financial market pressures through operations such as quantitative easing. Thus, although markets can influence rates to adjust the risk premium, their impact remains marginal compared to the power of central banks.

It follows that the sustainability of public debt depends on political decisions, on the goodwill of the ECB. Neither the level of public debt nor that of interest rates really restrict the fiscal space of States, because the ECB can, at any time, decide whether a country can continue to spend or must default, regardless of its level of indebtedness. The example of Greece is revealing: in 2010, when its debt/GDP ratio reached 130%, the country was facing a crisis. By contrast, by the end of 2021, with the ratio above 200%, the issue of public debt was no longer an issue. This demonstrates that the sustainability of public debt is primarily a political, not an economic, issue.

There is no link between public debt levels and growth

A recurring argument in discussions on public debt is that there is a debt threshold beyond which economic growth is compromised. However, no rigorous research has ever confirmed the existence of such a threshold. As Yeva S. Nersisyan and L. Randall Wray5 show, “There are no thresholds [of public debt levels] that, once crossed, will be unsustainable or will reduce the country’s growth.” In fact, economic history is full of examples where high levels of public debt have coexisted with sustained growth, as long as the state maintains active economic support.

Liz Truss’s resignation, a good example of the lack of foundation for the influence of financial markets

What happened in England in 2022, leading to the resignation of Prime Minister Liz Truss, is a striking example of how financial markets can influence political decisions, even if these decisions are not necessarily dictated by real economic constraints. In reality, the pressure from financial markets was stronger than economic considerations, which perfectly illustrates the power of the financial system over politicians. Fear of the market reaction prevailed over economic issues6.

Rating agencies: what legitimacy?

The intervention of rating agencies consolidates the dominant idea that it is imperative to appease financial markets, whatever the cost. These agencies, private companies operating without real democratic control, are given an outsized role in the evaluation of public finances. Their influence, often considered infallible, shapes the budgetary policies of States, and their decisions directly impact economic choices. However, neither their competence nor their integrity are systematically verified. Entrusting these private entities, effective promoters of the dominant neoliberal thinking, with the ability to decide on the budgetary future of a country constitutes a serious breach of the principle of national sovereignty, and a real denial of democracy.

Conclusion: deconstructing the ideological influence of financial markets

At the end of this analysis, it is obvious that the excessive importance given to financial markets in the budgetary choices of Eurozone Member States stems from self-imposed financial constraints, and that this situation gives illusory power to the markets, with the final decision always belonging to the ECB. By locking themselves into a logic where they are forced to « please » the markets to finance their spending, Member States are depriving themselves of an essential lever to stimulate their economy and meet the needs of their population.

This dependence on financial markets masks the political reality behind the sustainability of public debt: at any time, the ECB can guarantee or not the issued government securities, which underlines the fundamentally political nature of this issue. Thus, it is not the level of public debt or interest rates that limits the room for maneuver of States, but rather the governance choices that prioritize the satisfaction of the markets rather than that of citizens.

The example of the COVID-19 crisis has shown the capacity of central banks to intervene to stabilise the economy, independently of the pressures of the financial markets. It is therefore essential today to reconsider the budgetary rules of the Eurozone, in order to restore the sovereignty of States and refocus budgetary policy on collective well-being, instead of giving in to the imperatives of the markets. By taking this direction, States will be able to fully use their resources to serve their citizens, leaving behind the illusion of market power that is in reality only an imposed political constraint.

NOTES

- This point is explained in this article: https://blogs.mediapart.fr/robert-cauneau/blog/181024/les-soldes-financiers-sectoriels

- For a more detailed explanation of this point: https://mmt-france.org/2020/07/25/fiche-n-7-definition-de-la-base-monetaire/

- Read this article by Warren Mosler: https://mmt-france.org/2019/04/23/le-taux-dinteret-naturel-est-zero-2/

- The link between the central bank’s key rate and the rate applied to government securities in 6 other countries is available here: https://x.com/robert_cauneau/status/1427693670992650246

- The article referred to can be found here: https://www.ofce.sciences-po.fr/pdf/revue/8-116.pdf

- A discussion between Steven Hail and Stephanie Kelton sets out this argument in this video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lADHLdjBESg